It is time to move away from the linear model of development and stop the avalanche of waste produced by the inhabitants of the most developed, most consuming countries. Unfortunately, that is easier said than done. Over the past decades, humanity has been guided by a paradigm of relentless GDP growth and economic development, which while bringing many benefits, has also brought us to the brink of an ecological abyss. Today, with the oceans filled with plastic, the air filled with smog, and greenhouse gases responsible for climate change accumulating in the atmosphere at a dramatically rapid rate, this is even more apparent than before.

This is where the need to step away from an economic model based on perpetual consumption and resource consumption. What in return? The European Union is proposing an alternative in the form of a closed-loop economy, often referred to as the circular economy. Its concept is simple: instead of flooding the market with disposable products that become useless after a short period of usefulness and end up in the trash, promote things that are long-lasting, durable and capable of being exchanged, repaired or used in different ways.

All this is to stop exploiting the earth in search of new raw materials and to keep them in circulation as long as possible – if they lose their use in one area, perhaps they can be recycled to be usable elsewhere. This translates into benefits not only for the environment, but also savings for the business. For example, manufacturing a can from scrap metal can save up to 96 percent of energy, and reduce water pollution by 97 percent.

The closed-loop economy aims to reduce the mass of waste that ends up in landfill every year. In light of EU directives and guidelines, the best waste is that which is not produced at all (this is the fundamental principle of the waste hierarchy. No waste means no waste-related problems, such as collection, transport or disposal – and all these methods require more or less money, energy and materials.

How can this be achieved? One of the solutions is to better design products to be more durable, made of materials that are easier to recycle and decompose into individual raw materials that we can use longer and better. In practice, this manifests itself as incentives to extend the life cycle of products, to encourage reuse, repair and remanufacture of products.

While the main principle behind the closed-loop economy is simple, its full implementation is not so easy. Poland still lacks legislation and appropriate tools that would strongly emphasise the need to reduce waste at source and reward reuse. The waste industry and the industry are still waiting for the development of mechanisms to support eco-design and the implementation of the new extended producer responsibility model. A decision has also not yet been taken on the introduction of a deposit system for plastic packaging. The implementation of the SUP Directive, which must be transposed into national law by July this year, is also in question.

The problems can be seen not only at a central level, but also at a local level. This is illustrated by a study carried out by the Supreme Audit Office, which examined how local authorities manage their waste management. The conclusions are not optimistic. The Supreme Audit Office’s analysis shows that in the majority of municipalities covered by the audit (15 municipalities over 2 years), other less desirable methods than recycling and preparation for reuse, were dominant in the management of municipal plastic waste. In 2018, landfilling was the main method in three of the five provinces audited (between 65% and 68% of the waste generated). In contrast, the two other provinces audited were dominated by thermal waste treatment (between 38% and 46%), also undesirable in the light of the EU and the waste hierarchy.

Today, legislation allows local authorities to support these activities by providing reductions in the monthly waste fee. According to the Act on Maintaining Cleanliness and Order in Municipalities, owners of properties with single-family residential buildings who use their own backyard composter are entitled to it. This is the approach taken by many local authorities, especially in rural areas, where the residents have suitable conditions for composting on their own. The situation is much worse in large cities, where the collection of biowaste is often illusory. This can be seen in the poor quality of biodegradable waste collected in high rise developments where, to make matters worse, the number of bins is sometimes insufficient in relation to the number of residents using them.

It does not have to be this way, as good examples from other countries prove. The French town of Besançon has set an example by recycling biowaste at source using individual (decentralised) and community composting facilities accessible to the public. The former is financed by a system of proportional fees based on the principle: pay for as much as you produce. So far, the town has succeeded in reducing waste by 30 percent and raising the separate collection rate to 57 percent. Currently, 70% of residents have a composter or use community composters.

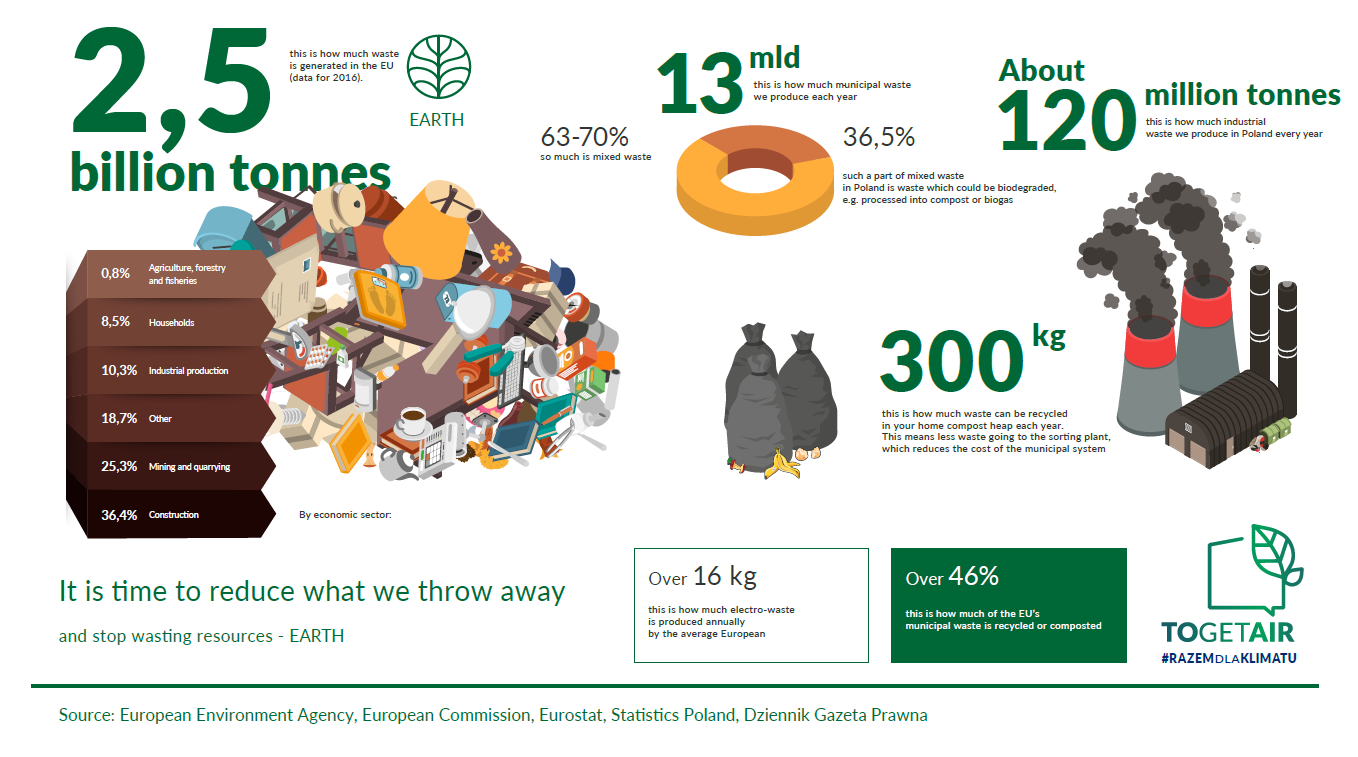

It is estimated that the average European produces 16 kg of electro-waste per year; globally, 50 million tonnes of unwanted electronics go to landfill every year. This is why we must start working today on regulations to extend the life cycle of products, above all, electronic and electrical equipment.

Often these products end up in the bin simply because it is not possible to replace the broken or worn out part, or the repair is so expensive that it is more cost-effective to replace the old device with a new one. Therefore, the new legislation should include measures to improve the durability of products and ensure the availability of information on repairs and spare parts. The legislation should also allow residents to enforce guarantees better and eliminate false claims about environmental impacts (greenwashing). A model for such a regulation can be found in Sweden, which back in 2016 introduced tax breaks for repairs to both household appliances and, for example, clothes washing machines.

Although recycling is not the most important objective of the closed-loop economy, it still ranks high in the EU waste hierarchy. And the effectiveness of recycling is mostly influenced by the quality and cleanliness of selective waste collection. This is not the best situation in Poland because, industry statistics indicate that from 63 to 70 percent of what is sent from municipalities to sorting plants is just mixed waste, from which only about a dozen percent of valuable raw materials can be recovered and sent for further processing.

Improving separate collection is a challenging task that requires the cooperation and commitment of municipalities, municipal facilities and the central administration, which is responsible for the legal environment. Throughout the EU, despite the same waste guidelines, there are examples of towns and cities that perform much better than others and can serve as a model. This includes Ljubljana, Slovenia’s capital, which has a door-to-door waste collection system – still not widespread in the EU but still the fairest – and fees proportional to the amount of waste generated (PAYT, pay as you throw). It encourages waste reduction at source and better segregation. It is worth considering allowing such a model to be used in Poland.

The Polish legislator and local governments must also prepare for the inevitable extension of the range of waste which will have to be separately collected to include, for instance, textiles (from January 2025). This will require the expansion of collection systems, as well as the adaptation of waste treatment facilities to be ready to accept much larger quantities of this particular fraction. France has already blazed a trail in terms of regulation, with its law on the closed-loop economy and the fight against waste adopted last February. It forces manufacturers in many industries (not only textiles, but also cosmetics, electronics) to take specific actions to reduce waste (in France, every year goods worth PLN 650-700 million simply go to waste). One of these is the inclusion of textile products in the extended producer responsibility scheme. This obliges them to cover the costs of collection and recycling across the country. The adopted legislation will require unsold products to be either recycled or donated to charity (rather than incinerated or landfilled, as is currently the case).

Western European countries’ experience shows that as the wealth of society increases, so does the level of consumption.

Similar processes are seen in Poland. Between 2000 and 2014, for example, the real level of consumer spending more than doubled. All this contributes to making the world more littered. Therefore, it is necessary to undertake extensive educational activities to promote pro-environmental attitudes among the inhabitants and encourage them to change their habits.

Author: TOGETAIR Editors